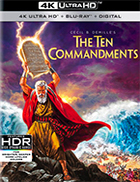

The Ten Commandments (4K UHD) [Blu-Ray]

|

Cecil B. DeMille's opulent Technicolor Biblical epic The Ten Commandments, a version of which he had previously directed in 1923, is the cinematic equivalent of really bad religious art: Those who love it and find it spiritually moving truly, deeply love it, while everyone else would think it just plain vulgar if it weren't so delightfully kitschy. DeMille, never one for subtlety (or good taste, for that matter), paints his blockbuster portrait of Moses leading the Hebrews out of slavery in Egypt with the brash masterstrokes of a true Victorian impresario—no vista is too grand, no King James-inspired line of dialogue too portentous, no moral too obvious. Yet, despite all this flamboyant grandiosity, the film has a strangely stage-bound quality, the result of DeMille's visual skills never having moved much beyond his beginning career as a theater director and his decision to stage the whole film like a pageant. In the silent era, DeMille was a virtuoso pioneer of lighting (see 1915's chiaroscuro-lit The Cheat, for example) and spectacle (too many films to list). But, while other cinematic visionaries forged ahead by exploring new possibilities for the medium, DeMille remained largely mired in a static aesthetic that favored postcard-ready posturing over movement and visual fluidity. Granted, he constantly fills the frame with awe-inspiring imagery, but you can always sense the frame itself (the movie's simultaneous grandeur and restrictedness is probably why it has played so well on television for so many years). The 1950s was the era of big-budget sword-and-sandal movies and Biblical epics, and with The Ten Commandments, DeMille wanted to make the biggest of them all. Budgeted at $13 million (about $125 million in today's dollars), it was half a decade in production, with massive sets, a cast of thousands, and location photography in Egypt where Moses himself had walked 3,000 years earlier (although so much of the movie was shot on sets with blue screens that the impact of the location photography is thoroughly overshadowed by the production's overall staginess). It was to be the last movie DeMille would make, and also his most successful. In fact, The Ten Commandments was the box office leader of the entire decade, unsurpassed until The Sound of Music (1965) a decade later, and one of the prototypes of the modern blockbuster. Charlton Heston, in the role that would come to define his career both cinematically and politically, stars as Moses from the time he is a young man until the day of his death just outside the promised land 40 years after liberating the Hebrews. Heston had already achieved leading-man status by that time, having worked primarily in anthology television dramas in the early '50s before landing half a dozen major roles in a wide variety of films, including The Naked Jungle (1954) and Secret of the Incas (1954), the latter of which was a major influence on the Indiana Jones franchise three decades later. His breakthrough came when DeMille cast him as a circus manager in his 1952 Best Picture Oscar-winner The Greatest Show on Earth, although it was his casting four years later as Moses that would transform him into a cinematic icon best known for playing stoic historical figures (he would win an Oscar three years later for playing the titular vengeful Jewish prince in William Wyler's Ben-Hur). With his chiseled features, upright demeanor, and commanding voice, he was the perfect choice (albeit not DeMille's first) for the movie's picture-postcard vision of Moses. In fact, the less Heston is buried under make-up and wigs, the more effective he is as an actor. When playing the young Moses, then a Prince of Egypt whose Hebrew ancestry is hidden by his adoptive mother, he is strong and virile—a true screen presence. DeMille is clearly intrigued by Heston/Moses's hypersexualized masculinity at this point in his character arc, otherwise he wouldn't have lavished so much time on the Egyptian princess Nefretiri (Anne Baxter) trying to seduce him or a shepherd's seven giggly Southern-fried daughters ooh-ing and ahhing over him as if they had never seen a man before. However, in the movie's second half, when Heston becomes "Moses the Biblical Icon" with the flowing white beard, he devolves into a near parody of stern moralism. Gone is the virility, replaced instead with dull stoicism and righteousness. In fact, you can witness the very moment when it all changes, which is also the movie's most inadvertently hilarious scene: After coming down the mountain where he heard God in the burning bush, Heston's close-cropped beard and short brown hair have been suddenly been replaced with a longer, grayish beard and an absurd gray pompadour that would look right at home on a cut-rate televangelist. It is as if, rather than returning from a face-to-face encounter with God, Moses has wandered in from a bad—and I mean really bad—day at the parlor. After that, you can track the passage of time through the graying and growing of Moses's hair and beard, which becomes ever bigger, fluffier, and more patently absurd the closer he gets to freeing the Hebrews. Unfortunately, that is the direction the movie heads as a whole, right into the realm of ham and cheese. Neatly divided into two halves—the first following Moses as a young man who gradually learns of his true heritage and is eventually expelled from Egypt and the second following his return to Egypt under God's command to free the Hebrews from slavery—The Ten Commandments runs for a ponderous three hours and thirty-nine minutes. In the process, it brings down with it a cast of notable actors, although a few manage to stand tall even with their portentous King James-inspired dialogue. These include Edward G. Robinson, saved by DeMille from the ravages of the blacklist, as the Hebrew turncoat Dathan and Yul Brynner as the pharaoh Rameses, Moses' hardened nemesis. Of course, what audiences really wanted in The Ten Commandments, aside from feel-good Biblical piety, was spectacle, and DeMille delivered all his budget would allow. Back in the silent era, DeMille had perfected the art of delivering sex and nudity within the narrative framework of moralistic Bible stories, a spectacle much different than what the more conservative 1950s would allow. When the Hebrews defy God and conduct an orgiastic paean to a golden calf at the foot of Mount Sinai while Moses is receiving the Ten Commandments, you can almost feel DeMille going back to his roots, wishing he could include a few naked breasts or a suggestion of lesbianism in there, just like the good ol' days. But, alas, the orgy has to be restricted to lots of drinking, wild carousing, and women riding on men's backs, but nothing more. Instead, DeMille fills the spectacle quota with scenes on a grandiose scale, such as the Hebrews' exodus from Egypt, which reportedly used some 20,000 extras, and big-budget special effects. For the movie's true climax, we get the glorious parting of the Red Sea, which at the time was considered the greatest image ever seen on-screen. DeMille was intent on using every facet of the cinematic medium at his disposal for the glory of mythmaking; it's as if his goal were simply to overwhelm his audience, which is perhaps why the movie gives you so little to think about when it's over. Today, the special effects in The Ten Commandments have a quaint, old-fashioned charm that belies the spiritual quality some people apparently saw in them. Perhaps audiences were deeply moved by the sight of Heston/Moses parting a sea or God as a cartoonish pillar of fire writing the Ten Commandments one by one on the side of the mountain, but it's hard to feel much gravity in a movie that is so consistently and unapologetically hammy. Despite DeMille's proclamations of serious intent, which he delivers in person at the beginning of the film like the true showman that he was, The Ten Commandments, for all its fire and brimstone, may be one of the cinema's greatest accidental comedies.

Copyright © 2021 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Paramount Home Entertainment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Africa Leader news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Africa Leader.

More Information